Greece's economic resilience test

PEPP has underwritten the economy under Covid; will the 'Lagarde put' do the same?

Last Christmas we noted how Greece had returned to the euro-area mainstream in 2020 thanks to the inclusion of its bonds in the European Central Bank’s emergency asset purchases. The ensuing financial stability meant the government could provide the fiscal support needed to get the economy through the first year of the pandemic.

This year, we’ve seen the macroeconomic benefits of that approach, with gross domestic product bouncing back strongly — despite pessimistic forecasts in the early months, when the country was still in lockdown. A solid improvement in summer tourism also helped to put quarterly GDP back above its pre-pandemic level and almost closed the gap with the trend.

But there are caveats to this rosy interpretation of the data.

Even though we know that at the aggregate level household balance sheets have strengthened considerably since the start of last year — as seen by the inexorable rise of household deposits — we don’t have good data to give us any sense of the distributional impact of rising total wealth.

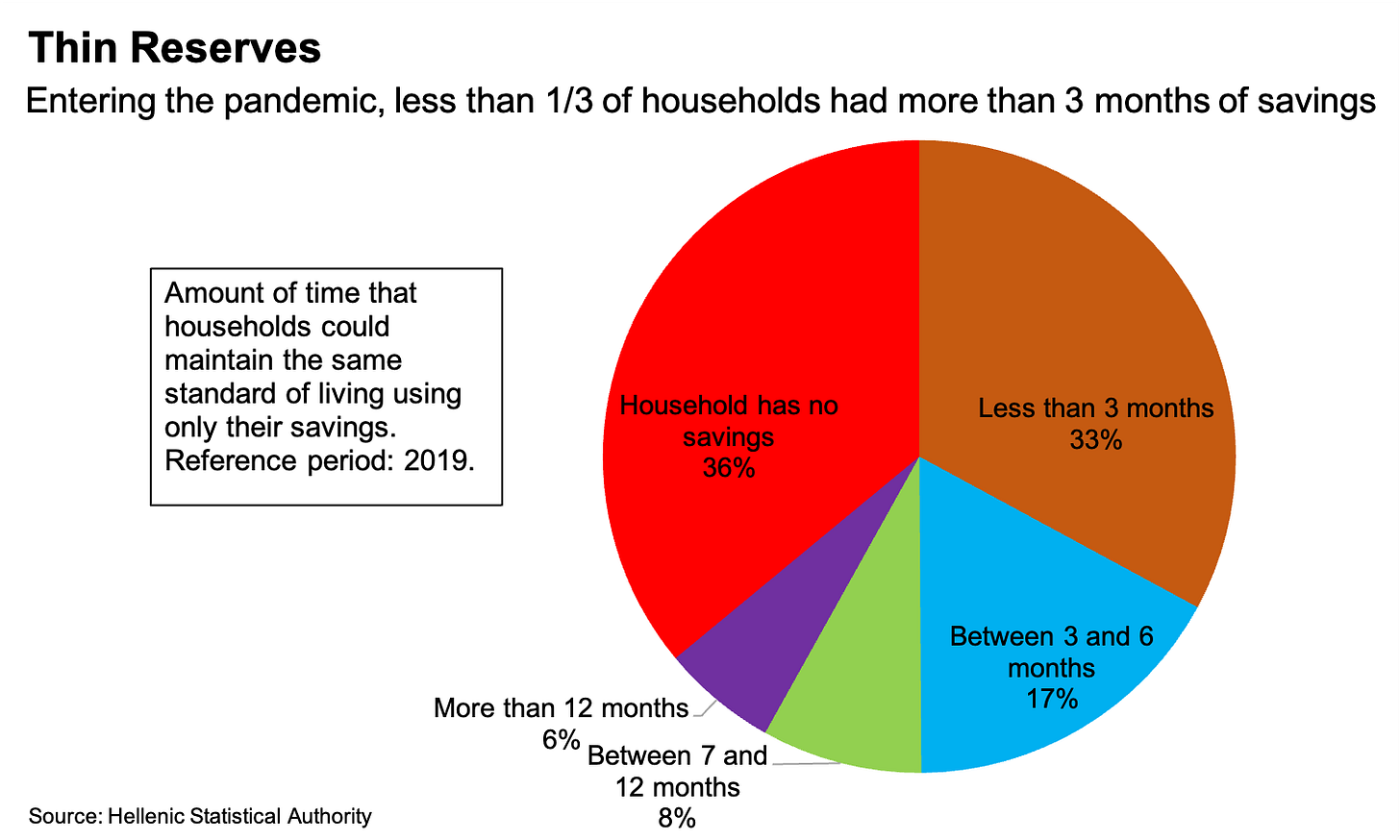

Just before the pandemic, 36 percent of households had no savings at all, according to the most recent Elstat survey of over-indebtedness, consumption and wealth. We don’t know how the pandemic affected that ratio, but it difficult to imagine that wealth inequality has lessened. My guess would be that the increase in deposits was heavily concentrated among those who already had at least some savings.

Lack of visibility on how widely shared the benefits of the rebound would be a major caveat on its own, but it’s compounded when combined with inflation’s reappearance.

This is probably the biggest topic in macroeconomics right now; it has been discussed a lot this year and will continue to be discussed in 2022. But wherever you stand on the debate over the current nature of inflation and how long it’s likely to last, when prices are rising quickly, it’s an aspect of economics that people perceive more readily than other indicators.

Putting these factors together can explain why, despite overall economic sentiment in Greece being at a 21-year high, consumer confidence is not much higher than it was during the 2020 lockdowns.

Inflation has become a potent political issue wherever it is present – in Greece just as elsewhere – and this will have a big bearing on policy in 2022.

New regimes

On the fiscal side, inflation is likely to put some wind in the sail of hawks for the big euro-area fight coming next year. That concerns the Stability and Growth Pact’s rules on debt and spending, which are suspended until 2023. That suspension enabled the Greek government to underwrite economic activity during the pandemic. The scrap over whether the rules should return as they were before, or in a different, less stringent guise will have a big bearing for the country.

As it is, Greece’s fiscal stance is set to tighten considerably next year. But to a large extent this is on account of the reduced need for that emergency support (as nicely set out in the chart from the European Commission below). As the SGP remains suspended next year, the government retains some leeway on the fiscal support it can provide if needed.

But either way, Greece’s apparent macroeconomic resilience will be tested in 2022 as the private sector is called on to pick up the growth baton, with reduced support from government spending.

It’s also likely that a bout of market turbulence will test Greece’s financial stability at some point next year. If the inclusion of Greek bonds in the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme brought the country in from the monetary policy cold, then the end of PEPP in March will probably make investors at least question how fully it has remained within that fold.

The yield on benchmark 10-year Greek government bonds is currently 1.34 percent, having dropped to a record low of 0.53 percent in August. The current level is more or less where it was at the start of 2020, just before the pandemic, and before the ECB started buying Greek bonds. But now the direction of (nominal) yields is going up instead of down (although real yields are dropping), and the biggest buyer on the market is set to depart the stage in a few months.

Of course it isn’t truly a departure, since the ECB said last week that it could reinvest cash from maturing bonds of other euro area states into Greek government bonds “under stress”.

But a promise to intervene when necessary is not the same as a buyer steadily hoovering up more than 1 billion euros of bonds a month, and it seems likely that markets will want to test what level it would take to trigger this “Lagarde put”.1

I’m signing off now until 2022. Happy holidays/καλές γιορτές everyone!

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback, either in the comments, on Twitter or by reply if you received the newsletter by email. If you’re not subscribed yet, consider doing so now.

After the “Draghi put”, whereby the power of Mario Draghi’s perceived commitment to do “whatever it takes” to keep the euro area intact was enough to stabilise the bond market.