The year Greece came out from the cold

Monetary policy allowed fiscal stabilisers to do their job in 2020

Beyond the abrupt shock caused by the coronavirus crisis, one of the big stories of 2020 for the Greek economy has been how fiscal and monetary policy worked surprisingly well together to prevent a much worse outcome.

The European Central Bank’s monetary expansion is the critical piece of economic infrastructure that’s supporting the “fiscal pipeline” we talked about a few weeks ago, which is keeping liquidity flowing to the real economy. It’s also part of the reason why household balance sheets have been able to strengthen, even as disposable income has taken a massive hit.

As the year draws to a close, this policy seems like natural common sense in the face of an unprecedented economic shock. But the last decade of crisis has taught us the hard way that there are few guarantees the euro area can muster a common sense response to a financial crisis.

Lifted Quarantine

The eligibility of Greek government bonds in the ECB’s pandemic emergency purchase program — which, reversing a spike in bond yields, brought the government’s borrowing costs down to record lows — ended the careful quarantine the ECB had placed the country in as part of the implicit bargain that allowed its then-president, Mario Draghi, to start a quantitative easing programme in 2015.

Like the pipes that run outside the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the ECB’s payments architecture allows us to see parts of the monetary plumbing that would normally stay hidden inside a currency area through the national central banks’ TARGET 2 accounts, revealing imbalances in the cross-border flow of funds within the Eurosystem.

In the previous two episodes of fast-rising Greek TARGET 2 deficits, these were proxy indicators of rising financial stress, as depositors pulled their money out of Greek banks and foreign financial institutions dumped government bonds. But this year, the rising deficit has instead come with bond yields falling and bank deposits rising — instead of a sign of stress, the rising deficit is a sign of monetary policy calming financial waters through central bank bond purchases and lending to Greek commercial banks on favourable terms.

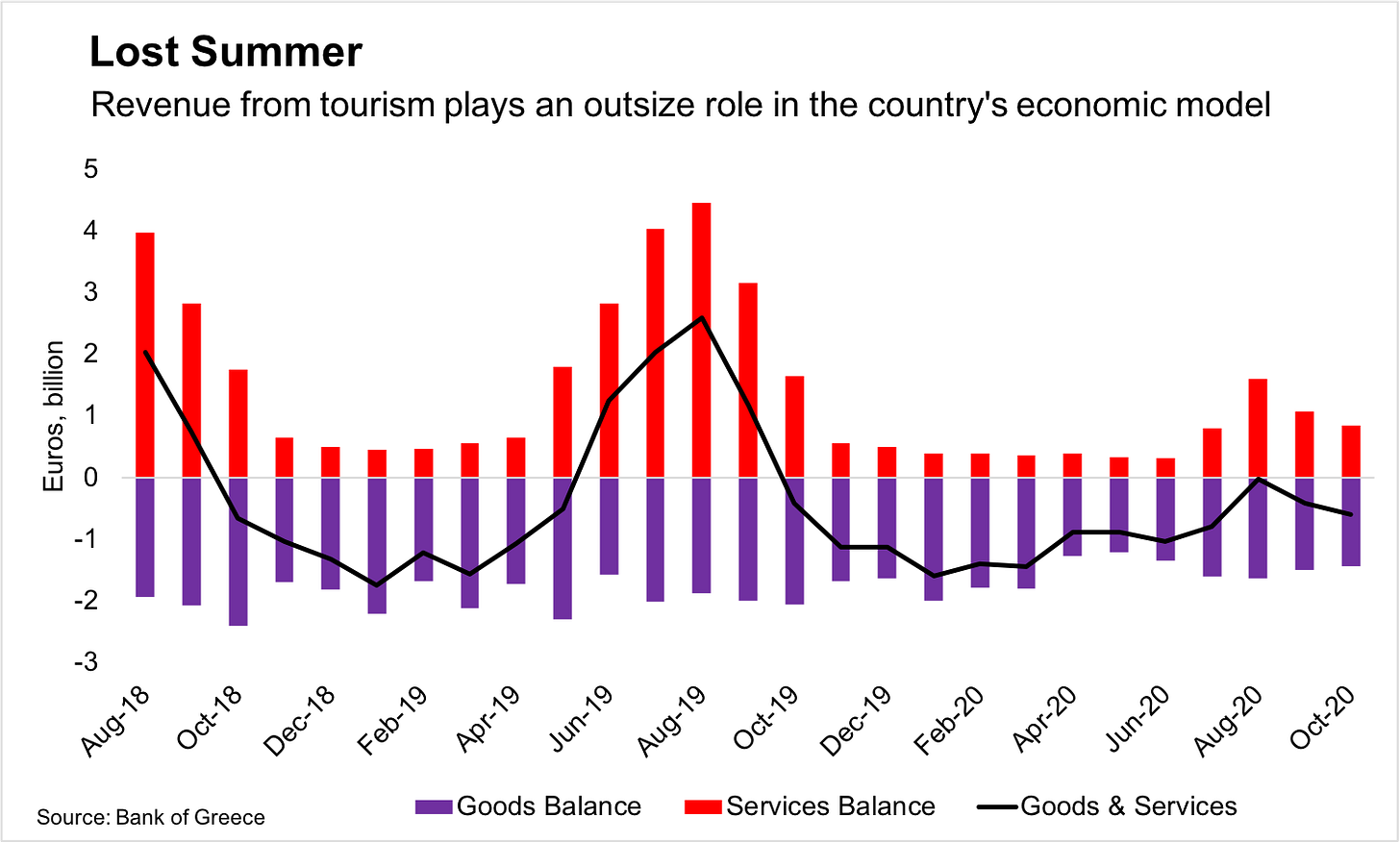

The Bank of Greece last week released balance of payments data for October, which taken in conjunction with the TARGET 2 data from the central bank’s financial accounts show that financial flows have been muted in recent months compared with the spring and early summer, when the central bank’s implementation of monetary policy was in full flow. In a welcome reversal of the experience of the euro crisis, early action from the ECB prevented the need for greater action later on.

The smooth functioning of monetary policy in 2020 has meant that — so far — there hasn’t been undue alarm over the resurgence of the dreaded “twin deficits”, in the government’s budget and the external current account. The political winds could well change in 2021 as Europe’s fiscal (and monetary) hawks are likely to eventually make a comeback. But in the meantime, Greece has some time and resources to reform an economic model that’s too reliant on tourism.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, consider sharing it with others who might also like it.

Upcoming key data

Thursday, Dec. 31:

October retail sales (Elstat)

Monday January 4:

December Purchasing Managers’ Index (IHS Markit)

Tuesday, Jan. 5:

November bank lending and deposits (Bank of Greece)

Thursday, Jan. 7:

December Economic Sentiment Indicator (European Commission)

Friday, Jan. 8:

November industrial production (Elstat)

November export and import of goods (Elstat)

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback, either in the comments, on Twitter or by reply if you received the newsletter by email. If you’re not subscribed yet, consider doing so now.