Macro roundup: Paying for it

The supply-chain choke is starting to put pressure on Greece's current account

The central bank released balance of payments data today suggesting that the global supply squeeze could play havoc with Greece’s external deficit if it continues long.

The value of imports jumped 30 percent in March compared with the same month of 2020. It’s a notable reversal, because in January and February, falling imports were what kept Greece’s current account deficit relatively in check. March’s increase — which can’t be explained by imports of oil products — was enough to bring the total for the whole first quarter higher than for the same period of 2020.

The current account deficit for the first quarter is still smaller — at 2.74 billion euros — than it was in the first quarter of 2020. But it’s a trend worth keeping an eye on.

As it is, the European Commission forecasts that the current account deficit will only narrow by 0.2 percentage points to 7.6 percent of gross domestic product.

My initial thesis when the data came out was that perhaps Greeks are starting to splurge some of the deposits piling up in bank accounts, buying bicycles and whatnot online — starting to play their part in the surging consumer demand globally that is a cause of the the supply choke. But looking deeper at the data suggests this puts the causality the wrong way around in the case of the rise in Greek imports.

The balance of payments accounts don’t provide much granularity on what’s imported. But the external trade figures from the national accounts do provide more detail — the numbers don’t match up exactly with the balance of payments data, but they come close enough.

That shows that two-thirds of March’s increase came from intermediate goods. Unfortunately, the Eurostat database doesn’t yet have volume data for the month, which would help verify the extent to which the increase is down to higher prices. However, we know from elsewhere that Greek manufacturers are facing higher input costs — something totally to be expected since it’s happening everywhere.

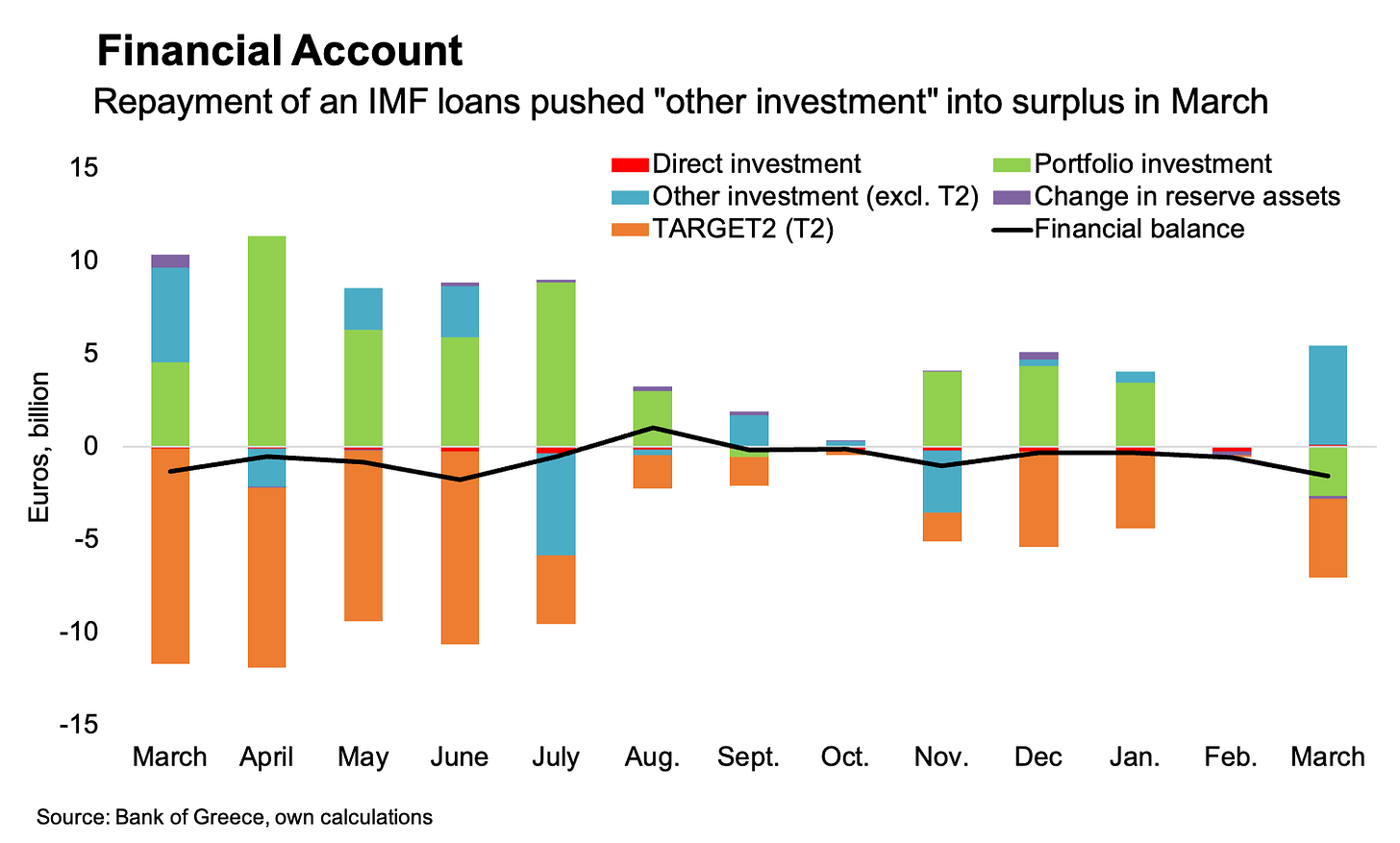

In the short to medium term, financing the current account deficit isn’t something we need to worry too much about. Greece’s return to the ECB fold has ensured the stable functioning of the monetary sector through the TARGET 2 system.

But it’s a fragile kind of stability. As we’ve noted since the start of this newsletter, the eurozone crisis was fundamentally a balance of payments crisis. It remains the case that until Greece transforms its economic model, it will always be especially vulnerable to economic currents from elsewhere.

Other data

Unemployment in January rose to 16 percent from 15.6 percent in December.

The state budget primary deficit for the first four months of the year came to 6.21 billion euros, below its target by 963 million euros.

Apartment prices increased an annual 3.2 percent in the first quarter, compared with 2.5 percent in the previous. It’s the first pick up in the rate since the first quarter of 2020, when apartment prices rose 6.7 percent.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, consider sharing it with others who might also like it.

Next week’s key data

Tuesday, May 25

January-April state budget execution, final data (Finance Ministry)

Friday, May 28:

Economic sentiment indicator (European Commission)

Elsewhere on the web

Reuters’s Karolina Tagaris has a good feature (with a terrifying headline) on bad loans, the banks and tourism.

Christian Odendahl, of the Centre for European Reform, and Adam Tooze have teamed up to write a brief on learning to live with debt.

The WWF has submitted a briefing to the European Commission flagging shortcomings in Greece’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

And here’s a highly enjoyable deconstructivist approach to inflation, brought to you by the excellent Center for Veb Account Research newsletter.

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback, either in the comments, on Twitter or by reply if you received the newsletter by email. If you’re not subscribed yet, consider doing so now.