Greece's tourism problem

Poor export diversity leaves the country too dependent on revenue from visitors

Greece today kick started a tourist season that just a few months ago looked like a write-off.

The government’s determination to salvage what it can from the summer is a gamble with its citizens’ health and its own reputation for handling the coronavirus crisis well. Such is the slight air of desperation to attract visitors that the government’s message has at times come across as confused about who can come and when, as it simultaneously tries to limit exposure to the worst-affected countries.

Yet given just how much the economy relies on tourism, the government’s willingness to roll the dice is understandable. The European Commission forecasts Greece’s economy will contract the most this year of any country in the European Union. Whole regions, particularly on the islands, depend on tourists for their year-round income.

On a day when some international flights resume and seasonal hotels open, it’s worth taking a step back and putting the government’s prioritisation of tourism in its proper financial context.

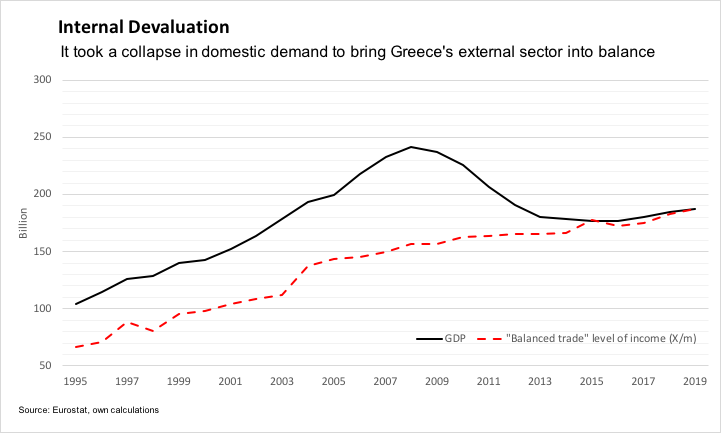

Despite the focus a decade ago on Greece’s huge budget deficit, the eurozone crisis was nevertheless primarily a balance of payments crisis. Greece’s free fall stopped and the economy stabilised when exports were brought into line with imports.

The chart below, compares GDP to exports divided by Greece’s import propensity, following Roy Harrod’s foreign trade multiplier. It shows how even the crisis of 2015 — when the white-knuckle ride following Syriza’s election led to forecasts for a double-digit recession — could barely shake the economy from its stable trajectory after the two lines converged.

What that story doesn’t show is just how much of the heavy lifting a massive boom in tourism did for Greece’s external adjustment.

Tourism revenue almost doubled after 2010, the year of the first bailout program, setting new records in six of the last seven years. The 18 billion euros brought in from international visitors last year represented a quarter of all Greek exports of goods and services. That ratio rises to a whopping 39 percent if you exclude two components with more questionable direct impact on Greece’s economy — oil (reexported refined petroleum products) and transport (Greek shipping’s outsize role in moving goods around the world).

So while it’s a truism that more visitors is good for the Greek economy, the problem is the poor diversification of the export sector, combined with a fear of what can happen when Greece runs a current account deficit.

Of course, countries can continue running current account deficits for as long as the rest of the world is willing finance them. But Greece is not a financial superpower with unlimited demand for its assets.

Looking for the positives, Greece’s inclusion in the European Central Bank’s pandemic quantitative easing program is a game changer in the short to medium term and will provide much of the balance of payments support the country needs. And if the European Commission’s recovery fund plan comes to pass, the fiscal stimulus it should provide Greece will be ample, without adding to the country’s debt burden.

But that particular chicken is yet to hatch. When EU leaders hold a videoconference meeting this week, the danger is that the only way to get the package past hawkish governments like the Netherlands will be by making assistance conditional on “structural reforms” that have become deeply toxic in southern European countries.

Even if Friday’s meeting delivers a positive result for Greece, how long will it be before we see a backlash from fiscal hawks reviving their cries that the EU shouldn’t become a transfer union? These voices are currently muted as the economic shock phase of the pandemic remains acute. But in 2009, too, the voices in the ascendency were those calling for Keynesian fiscal stimulus in response to the global financial crisis.

It’s uncomfortable watching the government using the low spread of coronavirus in Greece as a selling point to attract visitors, many of whom will inevitably introduce the virus with them. But with uncertainty still hanging over whether the EU will actually rise to the economic challenge, it’s forgivable that the government hopes Greece’s export champion can keep its external balances in check.

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback in the comments or on Twitter. If you’d like to read more posts like this, consider subscribing to the newsletter.