Housing and financial stability in Greece

The legacy of the country's pre-crisis credit boom remains with us

Last week was a quiet week for economic data, so instead of a normal roundup focusing on current releases, I decided to look some more at rising house prices. That turned into a bit of a safari in search of sources of financial fragility in Greece.

We looked recently at the increase in apartment prices, noting that they are getting close to where they were at their pre-crisis peak in 2008 — particularly in Athens.1 Then I brought up the b-word.

Here’s what I wrote:

But the other question is what implications this has for financial stability. The term “bubble” gets overused generally. When apartment prices started rising in Greece a few years ago, the term didn’t seem apt then. But when prices are now almost back to their pre-crisis levels — when they certainly were in a bubble — and that increase isn’t matched by a similar recovery in other metrics, then that at least begs the question of whether we’re in a bubble again.

It would be fair when reading that paragraph to infer that I’m suggesting that my answer to the question is: yes, real estate prices are getting bubbly again.

But I want to row that back a bit. A bubble is something that we identify in the rear view mirror, after it has burst. It seems that in every country you look, the rising price of homes is a contentious issue. If the market is about to crash, it’s more likely to be as part of a global phenomenon — and I see no good reason to consider Greece’s real estate sector as the canary in the coal mine for that. Housing is getting expensive for Greek residents, but that doesn’t mean it is going to get cheaper.

Sectoral balances

That paragraph from my original post seems a bit clumsy when I reread it, but the main question I wanted to raise is what, if any, implications Greece’s booming real estate market has for financial stability.

One lens through which to see a country’s economy is through its sectoral accounts. The net lending positions for a country’s private sector, public sector and the rest of the world must sum to zero, as a matter of accounting identity. It is often the case that when a country has a deficit with the rest of the world, and its private sector is also becoming more indebted, this pattern can lead to increasing financial fragility that can lead to a crisis further down the line. In Greece, we’re used to hearing about “twin deficits” — a current account and fiscal deficit. But what happens with the private sector also matters.

That’s the situation that Greece finds itself in at the moment. One of the most alarming charts I’ve made this year is of the country’s sectoral accounts, with the Finance Ministry’s projections through 2026. Under the government’s scenario, the external deficit will still be 5 percent of gross domestic product then — an amount corresponding to the private sector deficit, since the government budget is forecast to be in balance by then. All forecasts obviously need to be taken with a pinch of salt, but if that scenario were to actually happen, I’d be worried.2

In broad brushstrokes, this is a theme that has come up a few times in this newsletter, but what we haven’t ever done is map out this general schema to specific financial vulnerabilities in Greece.

Depth unknown

So a better question than whether Greece’s real estate market is in a bubble would be: is there a channel through which apartment price growth could expose Greek financial vulnerabilities?

The first thing to note — which I did in my original post — is that Greece’s pre-crisis housing bubble was fuelled by mortgage credit. Today’s increase in house prices it’s happening despite a never-ending credit crunch in the sector.

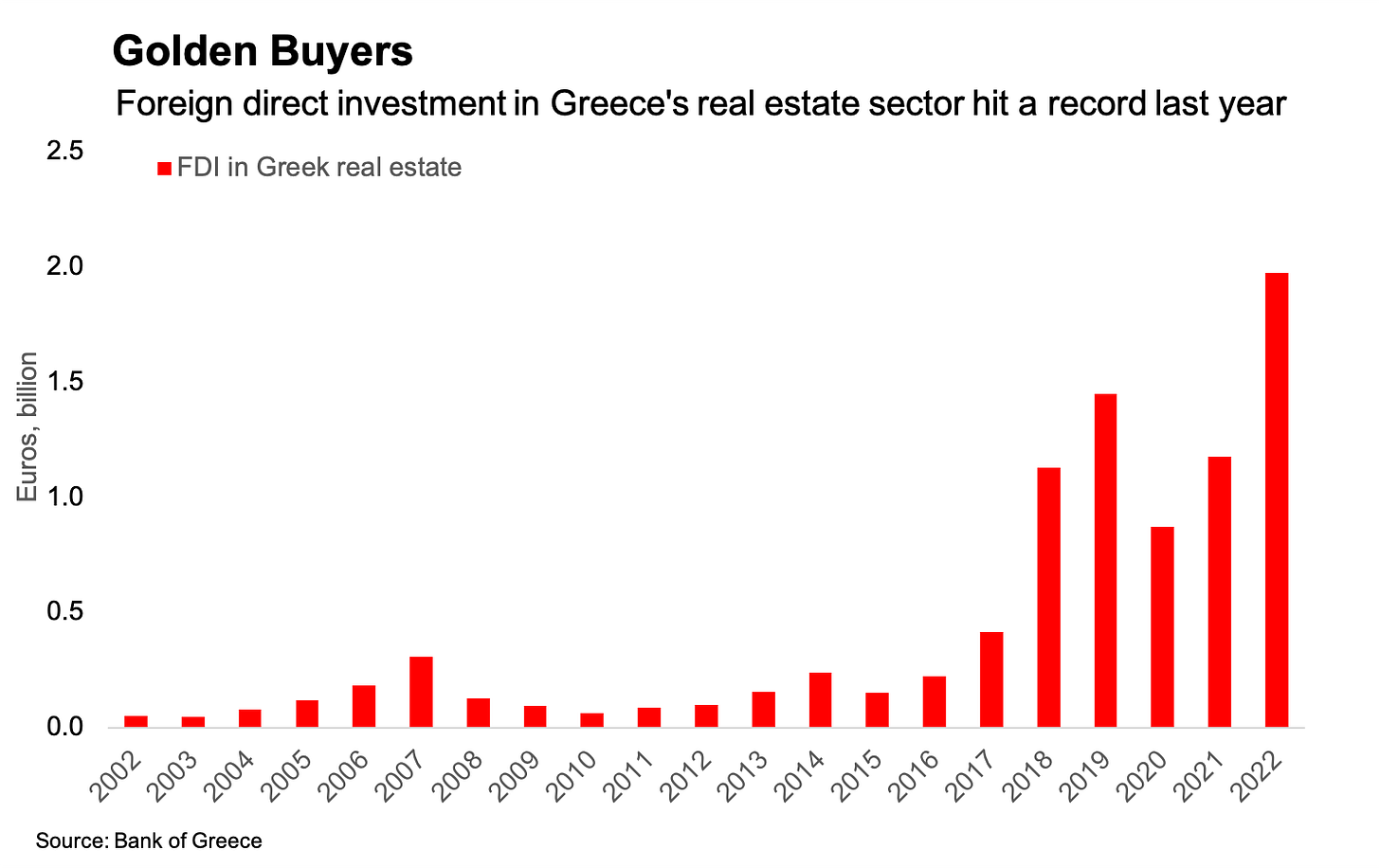

Instead, it seems that much of the capital injection into Greece’s housing market is coming from overseas buyers. Foreign direct investment into the country’s real estate sector hit a record of 2 billion euros last year.

At this point, we run into a common frustration when covering the Greek economy, which is the paucity of available official data. The Bank of Greece gives us the apartment price index, but nothing on the volume of transactions, which would give us some sense of market depth.

This matters in particular because while real estate FDI total may have hit a record, the number is still small when compared with the net flow of housing loans in the years before the crisis. That peaked at 12.3 billion euros in 2007.

While there should be some kind of multiplier effect from FDI inflows, it’s hard to get any kind of sense from publicly available data of how much of a role Greek residents’ equity is playing in the market right now, or of how big the impact would be if the FDI flow dries up.

However, going back to our search for a transmission channel from the housing market to financial instability, we can say the following: the traditional story of loans extended during the boom part of the cycle turning sour and bringing down bank balance sheets during the bust doesn’t apply here. That won’t be the case because bank lending just hasn’t played a role in the current cycle.

FDI inflows are also dwarfed by the size of the current account deficit, which came to 20.1 billion euros last year. When it comes to tracing the links between the growing indebtedness of Greece’s private sector and the country’s external deficit, non-residents snapping up Greek properties barely registers.

Who owes what to who?

Here we run into another problem with the data. The place to look for those linkages would be in the flow-of-funds accounts published by the Bank of Greece. Unfortunately, there’s a massive statistical discrepancy between the net positions of the sectors found in these accounts and those found in the national accounts produced by the Hellenic Statistical Authority.

For instance, in the flow-of-funds accounts, Greek households ran an overall surplus of 4.32 billion euros last year after increasing their deposits and reducing their debt. However, looking at data from the national accounts, the sector had a deficit of 11.2 billion euros. That’s a statistical discrepancy equivalent to 7.5 percent of GDP.

It’s a shame since the national accounts don’t give any indications of financial flows between sectors. If the two sources could be reconciled, the flow-of-funds dataset would be an extremely powerful tool.3

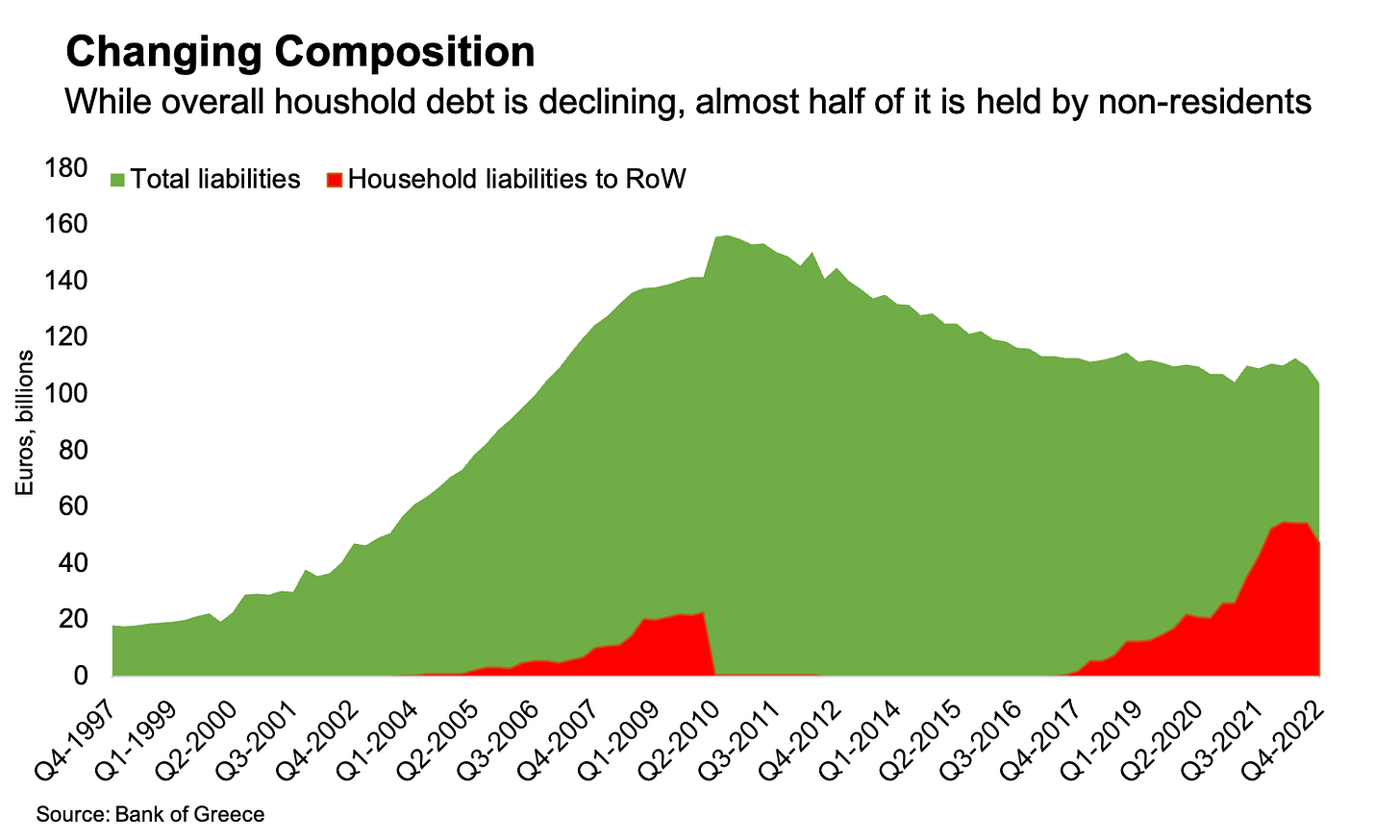

Using the same set of accounts, things get interesting when we look at what has happened to the stock of liabilities over the last few years. Although overall private-sector debt has been stable — and overall household debt has gently declined — the proportion of this held by the rest of the world has surged. It now accounts for about a third of total private sector and half of household liabilities.

This is entirely due to the banks’ securitisation programmes of the last few years, in which they sold portfolios of bad loans, removing them from their balance sheets. This programme has been heralded as a huge success in transforming the country’s lenders. Greek banks’ non-performing exposures — loans that are or more than 90 days in arrears or have recently been restructured — peaked at almost half of total loans in 2017. The percentage of NPEs to total loans is now back down to single digits as a result of the sales, and their restored health has made Greek bank shares one of the best performing investments in Europe this year.

Out of sight, out of mind?

One thing that this survey underlines is that while the crisis legacy of soured loans may appear to be a “solved” problem as far as Greece’s banks are concerned, these debt still exist and remain with us.

In terms of the rationale for the securitisation programmes, getting bad loans off the banks’ balance sheets was just supposed to be the first stage in the process. The idea was that the introduction of new investors into this market would help with the next stage, which is to restructure these loans and reintegrate distressed debtors into the financial system.

Back in April I attended the Delphi Economic Forum, and one of the panels I listened to was about the secondary market for these loans. The discussion is well worth a listen for anyone who’s interested in the subject.

A clear theme of the discussion was that the results of this second step have so far disappointed. It’s also clear that the banks would actually like these loans cured and back on their books. In the words of one of the panelists: “banks have tons of liquidity and nobody to lend money to”.

Source of risk

We started this post with a comparison between the current housing market and Greece’s pre-crisis real estate bubble, and we end it with a look at non-performing loans, many of which are a legacy of that lending boom. Along the way, we’ve asked whether there is a channel through which current apartment price growth could expose financial vulnerabilities.

We haven’t answered that, but it’s a question worth thinking about. What follows is pure speculation, but it’s a sketch of what such a channel might look like:

If Greece’s housing market is being propped up by foreign buyers, then prices are likely to drop if that foreign interest disappears.

This will affect collateral valuations and depress the secondary market for non-performing real estate loans.

Potentially, losses are confined to investment funds that bought the riskiest notes from the securitisation transactions.

In an extreme scenario, losses are also borne on the senior notes, which returned to the banks with government guarantees.4 Since these are contingent liabilities of the state, this then adds to public debt.

There is a related scenario where, in the absence of protections for primary residences, this also leads to a foreclosure crisis. This is a risk that Greece’s political opposition tried to turn into an election issue, without gaining much traction. For their part, financiers involved in the sector say that a glut of home auctions would crash the value of residences and so be against their own interest. They insist they see foreclosure as a last resort, and as a needed tool to prevent strategic defaults.

Short of a social crisis, an alternate scenario is that the banks may get their wish of getting these loans back on their balance sheets, but they turn bad again in the next housing market downturn.

But it’s possible that the greatest risk here is just that the private debt overhang continues to weigh over Greeks, limiting access to financing and acting as a drag on economic growth.

Last week’s data

Industrial production increased 1.4 percent in May from the same month a year earlier, compared with 4.1 percent in April.

Manufacturing increased 5.7 percent; electricity supply dropped 12.3 percent.

Industrial import prices fell 20.8 percent in May from a year earlier, compared with a drop of 17.5 percent the month before.

Biggest price drop was in crude oil and natural gas, which fell 41.6 percent.

This week’s key releases

Monday, July 17:

January-June preliminary central govt budget execution (Finance Ministry)

Friday, July 21:

May balance of payments (Bank of Greece)

A few people pointed out that the gap with the pre-crisis peak is larger when adjusting for inflation. It’s true that if you consider that the index of EU-harmonised consumer prices increased about 20 percent during the period of comparison, apartment prices are still about 28 percent lower than before the crisis in real terms. I think the key thing is that when you’re looking at nominal quantities, your comparisons need to be with other nominal quantities. In this case I looked at nominal household disposable income, which is about 20 percent below its pre-crisis peak, compared with 14 percent below peak for nominal apartment prices. Since people don’t choose between buying a house or buying a loaf of bread, I didn’t see the need to adjust for inflation. If we do, we also need to adjust disposable income in our comparison, and that’s still 34 percent below its pre-crisis peak in real terms.

There is a rosy version of the Finance Ministry forecast scenario whereby capital flows — including funds from the European Union’s Recovery and Resilience Facility — are ploughed into investment projects that transform Greece’s economic model and set it on the road to eliminating its structural current account surplus beyond 2026. Hopefully that’s how things play out. We’re overdue a post on investment — so we can look more at this soon.

For what it’s worth, the data shows non-financial corporations increasing their indebtedness — but to domestic residents. They decreased their debt to the the rest of the world, but increasing their liabilities overall thanks to a 6.18 billion euros flow into unlisted shares and other equity. That’s a figure that lines up very closely to the inward FDI recorded in the balance of payments in 2022. Households ran a small deficit against the rest of the world thanks to drawing down overseas deposits. Combining these two sectors, the non-financial private sector ran a deficit of 3.7 billion euros against the rest of the world. Against all other sectors, the non-financial private sector swung into a deficit of 2.66 billion euros in 2022 from a surplus of 15.1 billion euros the year before. By comparison, the national accounts data instead shows the non-financial private sector moving into a deficit of 12.4 billion euros from a surplus of 1.61 billion euros.

There’s a lot of financial engineering involved that I haven’t gone into here.