Macro roundup: Fighting over Greek debt

An old row between the ESM and the IMF's former Europe boss gets a new epilogue

It’s been a fairly quiet week in terms of macro releases, but a blog post by the European Stability Mechanism’s chief economist, Rolf Strauch, arguing that Greece’s debt is sustainable, has been doing the rounds.

The first question that sprung to mind on hearing about the blog: why is he writing this now?

While he doesn’t name names, the answer there must surely be that this is a response to comments last week from Poul Thomsen — the International Monetary Fund’s European director until his retirement from the fund last summer — that Greece’s debt will have to be restructured.1

Thomsen, who before becoming European director was the IMF’s mission chief to Greece at the time of the country’s first two bailouts and 2012 debt restructuring, dismissed the Greek debt sustainability analyses produced by the European Commission and ESM that focussed on debt levels many decades into the future.

Any solvency problem can be shown to be a liquidity problem if you allow a projection period for many decades. That’s not credible, and creditors would, of course, not consider it credible. They would know the country would be a sitting duck, for decades, while debt is slowly coming down, waiting for the next crisis to blow it off course.

But in the euro area, creditors have been willing to accept it. Why? Because they know they will be bailed out.

It’s against the backdrop of these comments that Strauch points out in his post that the ESM holds 55 percent of Greek debt, and that the average weighted maturity of this debt (plus that of its predecessor, the EFSF) is 31 years.

In fact, Stauch is taking a pretty conservative stance when he points to the ESM’s holdings. If you look at all of Greece’s bailout loans — including bilateral loans from the first bailout, EFSF loans and what IMF loans still remain outstanding — the country’s “official sector” debt amounts to about three quarters of the total. This is before we get to the fact — which we discussed last week — that the European Central Bank now holds almost a third of Greek government bonds.

If Greece’s creditors are willing to accept Europe’s debt sustainability analyses for the country, it’s because they’re the ones writing them.

The private sector creditors holding Greek bonds are doing so not just because they know the ECB is in the market buying them — though obviously that’s an important factor — but also because they know that if the country does have a debt problem, they’re only a small part of it. Haircutting bondholders won’t solve anything.

Stauch also notes that the cost of servicing this debt is much less onerous than the headline figure implies.

Like many other countries, Greece is benefitting from a secular decline in interest rates resulting in very favourable financing conditions. Historically low interest rates have reduced the debt service burden both as a share of overall expenditure and compared to taxation. In many respects, this is a new world for debt sustainability analyses.

To back this point up, he includes a handy chart:

Thomsen’s focus on the long-term nature of the European institutions’ DSAs is also a little rich, since the IMF fixates on long time horizons in its own DSAs. What the disagreements in the past few years between the IMF and European institutions in large part came down to — apart from the fund’s more pessimistic macroeconomic assumptions — was the fund’s greater focus on the long-term debt-to-GDP ratio. The European institutions instead concentrated on medium-term gross financing needs.

The third bailout programme ended in 2018 with the IMF never consummating its participation in the form of extending new loans — a fabled “red line” for Germany, right up to the point when it wasn’t. Greece was caught in the middle of a dysfunctional relationship between a Eurogroup dominated by Wolfgang Schaeuble’s force of will, European institutions and the IMF.

Ultimately, the IMF stayed out to the end, pointing to a murky picture for debt sustainability in the 2030s and beyond. The Eurogroup, on the other hand, was content to just revisit the matter in 2032.2

Through this all, the positions taken by Thomsen — the person who probably came to most personify “the troika” in Greece — always made most sense to me when they were viewed through the prism of a personal desire not to be “the meat in a future mea culpa sandwich”. Now that he’s retired from the fund, that lens is no longer helpful in interpreting these latest comments. Instead, they suggest a true believer in the danger of state over-indebtedness.

But there is one very important sense in which I fear that Thomsen will be proved right — that the eurozone’s politics of pandemic economic support measures will turn ugly once the acute phase of the crisis is over, and when that happens we’ll see austerity rear its head again.

“There will be pressure for more austerity down the road — significant pressure for austerity,” Thomsen said. “Of course, this is politically unsustainable and of course there will be strong tensions, north-south tensions and pressure for debt restructuring.”

There is some foreshadowing of this in Strauch’s post:

Once recovery takes off, Greece should return to the budgetary objective agreed with euro area partners, as long as fiscal adjustments do not entrench the economic scars of the pandemic. Greece’s long-term fiscal objective of a strong budgetary position in line with the European fiscal framework will create a fiscal buffer that will prevent the country from slipping into a low-growth environment during future crises and market convolutions. This leeway will earn Greece substantial market trust.

You can see where the battle lines will be drawn in coming debates in the parts of that passage I highlighted in bold. At what point does fiscal adjustment entrench the scars of the pandemic, and what should Europe’s post-pandemic fiscal framework be, are questions that will be hotly contested.

Data summary

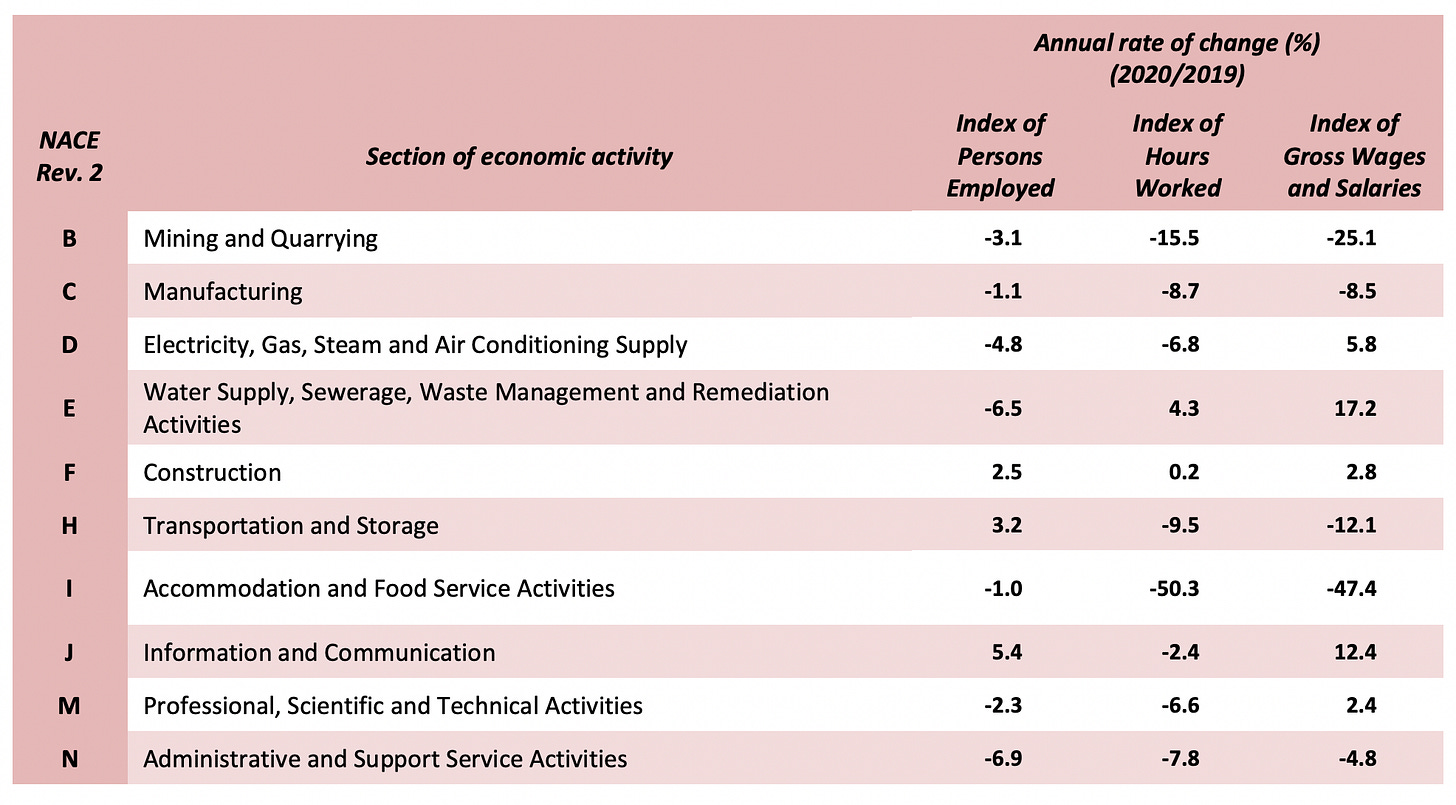

The release of January’s unemployment numbers was postponed, but Elstat did put out some other labour market stuff. Among them, this sectoral breakdown for the fourth quarter is useful. Note that construction was the only sector where both hours worked and persons employed increased, backing up some of the confidence we’ve seen coming from the construction industry.

Speaking of construction, building activity in January, as measured by permits issued, increased 6.4 percent from a year earlier.

The central government’s primary budget deficit for the first quarter was 3.42 billion euros. The noises from the Finance Ministry are less panicked about this than they were a couple of months ago.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, consider sharing it with others who might also like it.

Next week’s key data

Tuesday, April 20:

February balance of payments (Bank of Greece)

Thursday, April 22:

First notification of 2020 fiscal data (Elstat)

Elsewhere on the web

I included a link a couple of weeks ago to the “Greece 2.0” proposal in Greek, with the full list of projects and reforms the government intended to finance through the EU’s recovery funds. Now it’s available in English too.

The IMF proposes “solidarity taxes” on the wealthy and very profitable companies to show solidarity with those hardest hardest hit.

Over at MacroPolis, Wolfango Piccoli of Teneo Intelligence writes for The Agora about the multiple policy challenges facing Turkey.

Adam Tooze has written a few things this month that make for really good reading. In his newsletter, he looks back on Mario Draghi’s early career (this one stems from an essay in Foreign Policy on Draghi and Janet Yellen being called back for one last job). Then in the London Review of Books he has a piece on the transformation of Paul Krugman. Different types of career, but put them together and it makes a kind of “whither MIT Economics” series.

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback, either in the comments, on Twitter or by reply if you received the newsletter by email. If you’re not subscribed yet, consider doing so now.

He didn’t just single out Greece, but said this of indebted southern European countries in general. But it was at an Economist conference marking 200 years of Greek independence, so this is where the discussion was focussed, and where the comments were picked up.

Schaeuble at one point dismissed the IMF’s debt sustainability concerns by scoffing that no one had a clue what would happen several decades hence.