Residential property market heats up

Growth in Greek apartment prices has picked up pace after last year's slowdown

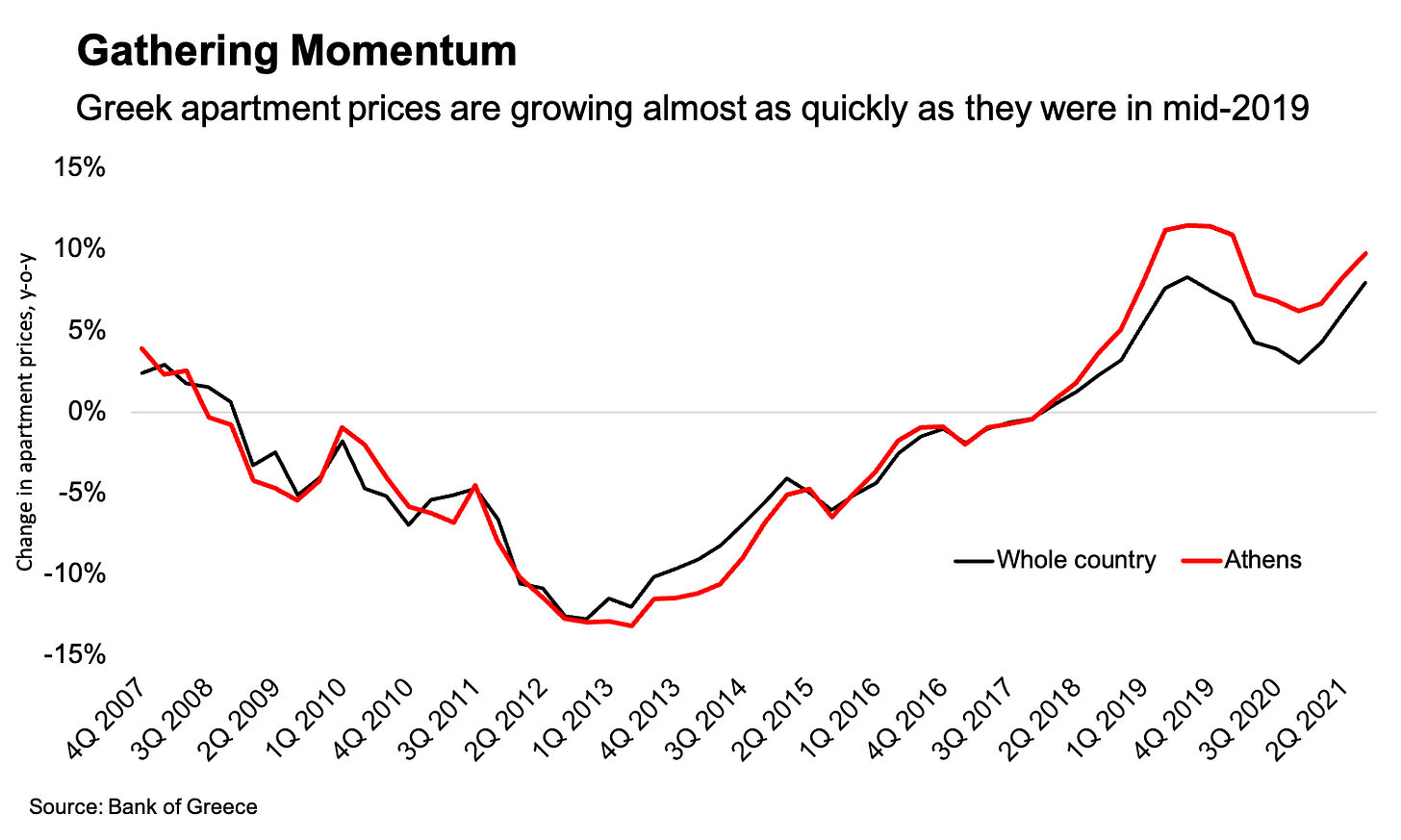

The interruption to last year’s house price recovery proved short lived.

Greek apartment prices rose 7.9 percent in the third quarter from a year earlier, the most since the same quarter of 2019, when prices increased 8.3 percent, according to Bank of Greece data this week. The second-quarter increase was also revised upwards, to 6.2 percent from 4.6 percent.

It shows that, as with many other aspects economic life disrupted by the pandemic, economic activity is picking up strongly where it left off.

The increases were most heavily concentrated in the country’s two biggest cities. In Athens, prices rose 9.8 percent, while in Thessaloniki they were up 8.7 percent. They rose 5.9 percent in other cities, and 5.7 percent in the rest of the country.

Catch-up growth

An instinctive reaction to a strongly-rising property market often tends to be to question whether a bubble is forming. One reason to not worry too much about that, yet, is that the market in Greece is still recovering from a deep depression. At its lowest point in 2017, prices had fallen 42 percent from their peak nine years before.

Since that low, prices have recovered 24 percent. That still leaves them 29 percent off of their peak.

Moreover, the collapse in house prices during Greece’s financial crisis was even deeper than the drops in both wages and disposable incomes. The recovery in house prices has tracked both of those indicators.

Another feature of the property market recovery is that it’s happening without much contribution from the banks. Mortgage credit in Greece is still contracting, so we’re not witnessing a lending-fuelled boom developing. The recovery will, however, increase the collateral value of the banks’ loan books, which could be a key factor for them getting out of the their own malaise.

What’s good for home owners and banks is, unfortunately, bad for renters.

The Bank of Greece doesn’t provide data on residential rents, and there seems to be an issue with the rent component of the inflation indices presented by Elstat. These have basically been flat for the last few years, which seems suspicious — both anecdotally, and from a common sense point of view.

That said, the comparison in property prices and rents is in many ways an apples and oranges comparison. Unlike buying a property, paying rent isn’t a one-off large transaction, but a series of recurring transactions each month. So even if rents are increasing for new tenancies, people on older contracts won’t see a change in how much they pay from month to month.

If there isn’t some mistake, that’s the best explanation I can think of for why no rent inflation has shown up in the consumer-price data. It would also explain the lag, at the start of the financial crisis, between the collapse in property prices and deflation showing up in the actual housing rent paid by tenants. Anecdotally, it seemed that rents were falling well before 2012.

Still, the fact that the index was completely unchanged for more than two years, until it started picking up a small amount in May, does raise an eyebrow. Housing rent has a fairy hefty weighting of 4.3 percent in the consumer price index basket. Back of the envelope maths suggests that an increase between 2.5 and 5 percent in actual rents paid by tenants would add between 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points to headline inflation.

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback, either in the comments, on Twitter or by reply if you received the newsletter by email. If you’re not subscribed yet, consider doing so now.