Guest post: Grading the Greek government's economic performance

Ahead of Sunday's elections, Dimitris Valatsas analyses the macroeconomic data to evaluate the incumbent's stewardship of the economy

This is a guest post by Dimitris Valatsas, of LGA - Lansberg Gersick Advisors. Dimitris — who has spent over a decade advising global corporates, hedge funds, asset managers and family offices on macroeconomic developments — writes the excellent Macro Letter, which you should subscribe to. Here, Dimitris turns his analysis to his native Greece ahead of the upcoming elections. In terms of the grades awarded, I don’t agree with all of Dimitris’s conclusion, so I will post some thoughts of my own on this later in the week — all in the spirit of hosting an open debate on Greece’s economy before the nation goes to the polls.

For voters, politicians, and economists alike economic performance is always in focus during electoral campaigns. The current campaign leading up to the Greek election is no exception — so for my guest post I will examine the economic record of the Mitsotakis government, which came to power in July 2019.

Photo by Constantinos Kollias on Unsplash

Before we dive in, a few caveats: globally, the period 2019-2023 is highly unusual from a macroeconomic perspective, due to the impact of the pandemic, the reopening, and the inflationary wave that followed. To the extent possible, I will try to compare Greece’s economic performance with that of the Eurozone over the same period. I will use seasonally adjusted data throughout.

I focus here on five distinct areas: gross domestic product, the labor market, real wages, investment, and inequality. I am deliberately avoiding any discussion of the deficit and the public debt load — in part because this issue receives ample attention as it is and in part because Greek debt dynamics are very peculiar. I am also avoiding any direct judgment on inflation (other than through real wages) given that exogenous inflation is beyond the government’s control, while endogenous inflation is primarily an issue for the European Central Bank.

GDP: a growth powerhouse

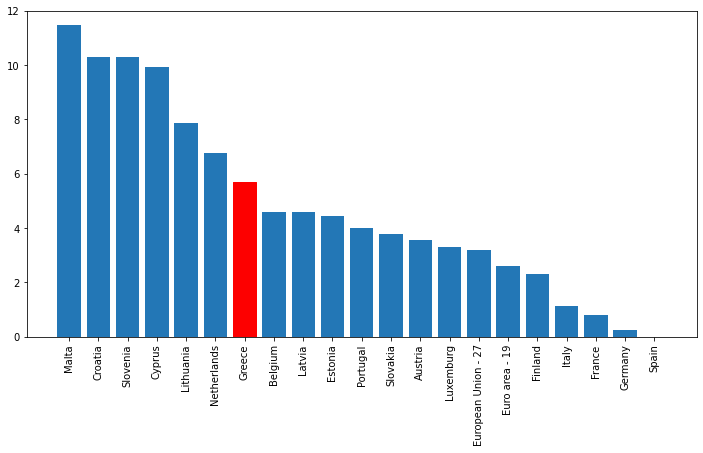

Like that of other European countries, Greek GDP declined substantially in 2020 and rebounded strongly thereafter. But since the Greek government took office in July 2019, we can look at the entirety of the period and compare its performance with that of other Eurozone members, who faced the same pandemic and the same monetary policy environment throughout.

Between the second quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2022 (the last quarter for which we have data), the Greek economy grew by a cumulative 5.7 percent in real terms, significantly higher than the Eurozone average of 2.6 percent over the same period and also significantly higher than regional peer Italy. The only country larger than Greece that performed better over the period was the Netherlands, at 6.8 percent.

In terms of GDP growth, it seems clear to me that the government deserves an “A” for stellar performance throughout the crisis and its aftermath.

Source: Eurostat1

Employment: more jobs across the board

Beyond GDP, employment is a key economic variable for any government. For Greeks, as for other Europeans, the employment situation has improved significantly since COVID. In fact, unemployment has been on a downward trajectory (from extremely high levels) since the peak of the Eurozone crisis in 2013. But because the headline unemployment rate also includes labor force participation data, I prefer to look at the total level of people employed, as I do for the U.S.

Source: ELSTAT

As before, COVID introduces an anomaly in the data, so to address the government’s record it is best to focus at the start and end-point, and to compare the country’s performance with that of the Eurozone as a whole. Since Mitsotakis took office in July 2019, the number of people employed in Greece has grown by a cumulative 276,600, or 7.1 percent of the starting total.

In other words, the Greek economy has been creating jobs at monthly pace of 6,200 jobs. (in U.S. terms, this would be equivalent to the economy generating about 193,000 jobs per month). This is down from 6,800 jobs per month on average created during the last Syriza administration (September 2015 - June 2019).

But again, we are focused here on the performance in 2019-2023, so it is better to look at Greece’s economic peers. To make the data comparable with Eurozone aggregates, I looked at the period 2Q19-4Q22. During that time, employment in Greece grew by 6.5 percent, compared with 2.6 percent in the Eurozone. Once again, Greek economic performance compares favourably with that of the rest of the Eurozone — the jobs growth rate is at least one standard deviation above the mean.

On jobs, too, therefore, I feel compelled to give the government an “A.” The Greek labor market weathered the COVID storm much better than other Eurozone countries, and has resumed strong growth since.

Real wage growth: work that doesn’t pay

Source: Eurostat

One area in which Greece is lagging substantially is real wage growth. Total compensation of employees has been increasing since the mid-2010s, and continued to increase under the current government. But this is a nominal measure— adjusted for inflation, the picture deteriorated significantly in 2022.

Source: Eurostat, Author’s calculations

Despite all that, real compensation of all employees has increased since the end of 2018 (I’m using the annual Eurostat dataset), by 1.75 percent. This is below the Eurozone average of 2 percent over the same period. However, this concerns total compensation — as we saw above, the number of Greeks employed has grown by about 9 percent over the same period. Assuming the data is directly comparable, this translates into a purchasing power loss of 7.25 percent per working Greek — a woeful performance.

Source: Eurostat

Part of this is a chronic issue with the Greek economy. At 35.2 percent, compensation of employees as a percentage of total GDP is one of the lowest in the EU — excluding Ireland, only Romania is lower. This number stood at 36.7 percent when New Democracy took over in 2019 and has deteriorated since.

Though part of it is probably explained by the fact that Greece has very high rates of micro-enterprises (where entrepreneur income would not be fully captured by salaries), this is an area of the economy where the government inherited a laggard and made things worse. I would give the government a “C” for real wage growth.

Investment: still low, but climbing quickly

Another key consideration for the Greek economy is aggregate investment, which collapsed from an average of 23 percent of GDP during the 2000s to an all-time low of 9.6 percent in the third quarter of 2015 — the infamous quarter of Greece’s referendum. To this day, Greece has the lowest fixed capital formation as a percent of GDP of any EU member state, at 13.7 percent of GDP.

Clearly, raising investment remains a critical issue for any Greek administration. However, as above, I have focused on the change during the period of the current government. There, the numbers are impressive indeed: the Greek economy invested 42 percent more in 2022 than it did in 2018.2

Note that these are nominal numbers — adjusting for inflation would bring the number to about 32 percent.

Source: Eurostat

Once again, Greece clearly made a lot of progress over the past four years. At 42 percent, the growth in fixed capital formation is almost 1.5 standard deviations higher than the Euro area average of 24.4 period for the period 2018-2022. Moreover, this is significantly more impressive than the prior government’s performance: between 2014 and 2018, Greek fixed capital formation increased by 4.2 percent, a full standard deviation below the EU average of 22 percent over the same period.

Greece remains a laggard in EU investment, but given the impressive growth, the government deserves an “A” for investment.

Inequality: doing better, with room for improvement

Another critical area of focus for any government (and the voting public) is inequality. There are multiple measures of inequality and the EU data is relatively patchy, so I will rely on three commonly used ones to assess the government’s performance: the S80/S20 ratio, the gini coefficient, and the poverty ratio.

The S80/S20 ratio divides the income of the top quintile by that of the bottom quintile. Greece has seen a sustained improvement since 2013, when the ratio was 7.46, to 5.61 today. It has converged much more closely to the EU average, which has gone from 5.33 in 2013 to 5.16 in 2021, the last year for which data is available. But most of that improvement was under the previous administration — the ratio was 6.07 in 2018 and fell to 5.59 in 2019.

Another metric is the gini coefficient, which measures aggregate inequality. A lower gini coefficient shows lower inequality. The latest data point for Greece is 31.4 — somewhat better. Once again, most of the improvement seems to have taken place under the previous administration.

Finally, I look at the percentage of the population at risk of poverty, which Eurostat defines as the share of people with an equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) below 60 percent of the national median. Here, too, the government appears to have treaded water, with most of the progress having been achieved during the previous two administrations (2012-2019).

Overall, the government took office as Greek inequality was improving; it made neither substantial strides nor took steps backwards. I would grade its performance on inequality as a “B.”

Summary: a strong economic performance in aggregate, but living standards need more work

Overall, the 2019-2023 macroeconomic performance is commendable. Greece is at the forefront of Eurozone growth; the economy continues to generate a substantial number of jobs; and investment, Greece’s Achilles’ heel, is finally picking up steam.

However, the distributional aspects of the economy show that the median worker has seen most of the benefits of economic growth taken away by inflation. To be fair, the government has compensated households (rather than workers) by a substantial amount of direct subsidies — it remains too early to judge how these will play out, but they seem to have helped take the sting out of inflation.

Inequality is also an issue that plagued Greece during the height of the crisis, when the poorest households paid a disproportionately high price. There has been substantial improvement in this regard, and the proportion of Greeks at risk of poverty is now much closer to the Euro are aggregate — though more can be done to bring this ratio down further.

The people vs. the data

The data overall paint a fairly clear picture of strong economic growth — comfortably above Euro area performance for the relevant period in both absolute and relative terms. But how this translates to the voting public is a different issue altogether.

According to a recent survey, 51 percent of Greeks think the economy is faring worse than it was four years ago, versus 45 percent who think it is faring better. Some 56 percent think their own household is worse off than it was four years ago, compared with 40 percent who claim to be better off. Finally, only 40 percent judge that the government has done a good job on economic growth — an astonishing judgment given, as we saw above, Greece is performing very well both vis-a-vis its peers and compared to prior years.

This is a reminder that, regardless of what the data say, public opinion can be swayed significantly by recent movements — Nate Silver has done some excellent work on this in the U.S. context. And of course, the economy is only one of many issues voters think about when they head to the polls.

I am excluding Ireland from the GDP charts and calculations because of well-known issues with its GDP statistics.

I use annual figures for comparison with other EU states here, but Greek fixed capital formation was flat on a quarterly basis between 4Q18 and 2Q19, when the current government came to power.