Macro roundup: Goodbye PEPP, hello reinvestment

New ECB tools are key for Greece as inflation brings tightening monetary conditions

The inflation horror show continued with another grim reading for March as prices in Greece increased an annual rate of 8.9 percent. Much ink has been spilt on this, and much more will follow given the painful situation for households.

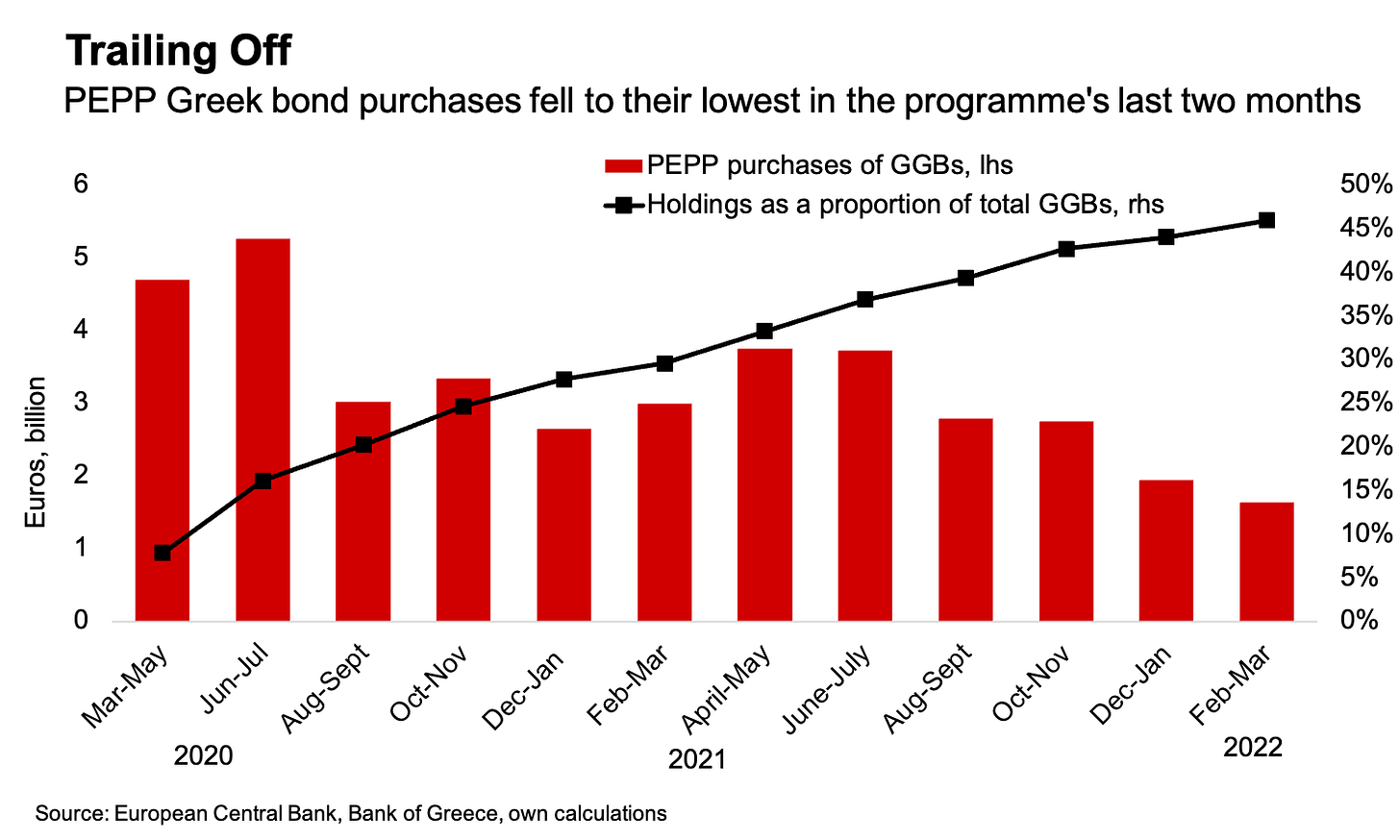

A little more under the radar, the European Central Bank released its breakdown of operations under the Pandemic Emergency Purchases Programme in February and March, showing that it bought 1.6 billion euros of Greek government bonds during these two months.

These two months are interesting because they were the last before the programme ended net additional purchases. The total purchased were the lowest of any two-month period since PEPP’s launch, marking a winding down of the programme.

Perhaps that’s unsurprising given that the ECB’s holding of Greek government bonds is now close to half of the total. But it marked a reduction of ECB support, and it coincided with a sharp rise Greece’s indicative borrowing costs. During this two-month period, the yield on 10-year Greek government bonds increased 92 basis points to 2.66 percent. It’s subsequently risen further to 2.84 percent.

Of course, the central bank will continue to purchase bonds under the reinvestment period that will run at least until the end of 2024. Crucially, there is scope to reinvest the proceeds from maturing assets into different types of assets to counter financial stress — meaning in theory that German bonds could be rolled into purchases of Greek bonds, which would translate into a de facto continuation of PEPP for Greece.

The unknown factor here is what circumstances would prompt such interventions from the central bank. Would it be an intervention responding to significant and obvious market stress, or will the ECB be proactive to avoid such situations arising?

We looked at this choppier environment at the start of the year.

The good news is that ECB executive board members are regularly communicating that they are taking seriously the problem of rising spreads between Greek and Italian bond yields over their German counterparts. In central-bank speak, this is described as “fragmentation”, and is a problem because it hampers the transmission of monetary policy due to factors beyond the sovereign’s control.

The ECB’s chief economist and executive-board member Philip Lane was in Greece this week to attend the Delphi Economic Forum. He addressed the issue in an interview with Kathimerini [emphasis mine]:

“The PEPP portfolio,” said the Irish economist, “amounts to some 1.7 trillion euros and the flexibility toward its reinvestment supplies some strong firepower. However, the ECB is quite clear: We are ready to use a broad range of means to tackle fragmentation. In the context of the Governing Council’s mandate, under the pressure of conditions, flexibility will continue to constitute an element of monetary policy anytime factors threatening the implementation of monetary policy put price stability at risk.”

That seems a clear statement that we can expect the use of more tools than just reinvestments as spreads widen. The next question this raises is whether these tools will be new ones, or whether the ECB will dip into its existing toolkit.

There has been some push for reviving Outright Monetary Transactions as a tool for the job — with the Institute of International Finance’s chief economist, Robin Brooks, banging this drum loudly.

OMT was the tool launched by the ECB in the wake of Mario Draghi’s “whatever it takes” comment. It helped narrow spreads, without ever needing to be used, by signalling the central bank’s willingness to act as a lender-of-last resort, prepared to make unlimited secondary-market purchases to backstop eurozone sovereign debt.

However, it’s seems almost inconceivable that OMT would be the tool, as it is currently constituted. There is a very good reason why it was never invoked during the eurozone crisis, which is that it requires that recipient countries enter a European Stability Mechanism programme — i.e. it comes with structural reform conditions attached.

It’s hard to overstate just how politically toxic this would be for any country entering the programme. It would entail a new “memorandum” — as Greeks called the bailout programmes — and would be a suicide note for any government that signed it. It’s hard to see how any countries would be prepared to sign up for that.

Other data

Greece’s EU-harmonised consumer price index increased 8 percent from a year earlier in March, while the index that applies national methodology rose 8.9 percent. On the national measure, electricity costs soared 79 percent, accounting for 3.1 percentage points of the total CPI increase.

Industrial production rose 4.8 percent from a year earlier in February, swinging back to positive after a dip of 0.5 percent the month before. Manufacturing increased 7.9 percent, which counteracted drops in electricity supply, water supply and mining.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, consider sharing it with others who might also like it.

Next week’s key releases

Tuesday, April 12:

First-quarter bank lending survey (Bank of Greece)

Wednesday, April 13:

February labour market survey (Elstat)

Friday, April 15:

Jan-March preliminary state budget execution (Finance Ministry)

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback, either in the comments, on Twitter or by reply if you received the newsletter by email. If you’re not subscribed yet, consider doing so now.