Keeping it real

Banks are flush with liquidity, but are businesses and households getting enough of it?

In the last post of 2020, we noted how monetary policy is allowing the Greek government to provide the fiscal stimulus needed to prevent a bad situation from getting much worse. But is that enough?

One person who doesn’t seem to think so is Bank of Greece governor Yannis Stournaras, who at an event last month reportedly lamented that European Central Bank liquidity isn’t reaching enough of the real economy. Instead, commercial lenders are increasing their government bond holdings and central bank deposits, while what is being channeled to the private sector is mostly going to large corporations.

Stournaras estimates that the growth in liquidity has been close to 40 billion euros, with only a small part of that reaching the private sector. That fits with central bank data released this week, which show that net credit flows to the private sector in the first 11 months of the year amounted to 3.8 billion euros.

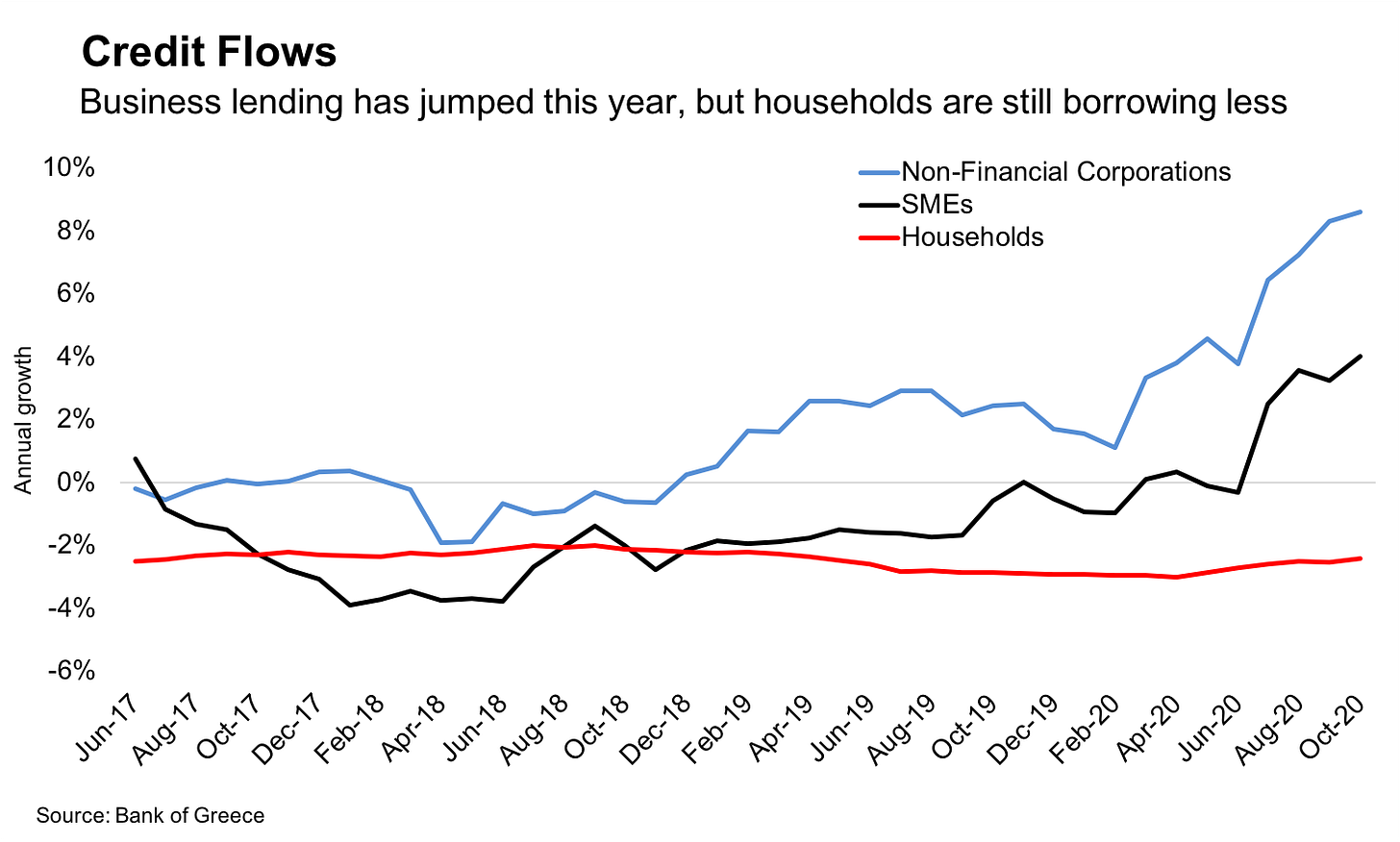

The data also back up Stournaras’s other contention — that most of the lending is being channeled to large corporations. While the annual growth in credit to the private sector as a whole in November was 2.6 percent, lending to non-financial corporations as a whole grew 8.7 percent, while for small and medium-sized enterprises it grew 4.6 percent. Net new lending to households contracted, as it has done continuously since 2010, declining by 2.5 percent.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, consider sharing it with others who might also like it.

The perennial question whenever there is insufficient lending to the real economy is whether the shortfall is due to weak demand or a reluctance on the part of lenders to take on credit risk. For Stournaras, the problem is the latter, with banks reluctant to issue new loans when they’re already heaving under the weight of bad debt that remains a legacy of the previous crisis.

The hit that businesses have taken from the coronavirus pandemic made a surge in demand for working capital loans inevitable. The central bank’s lending survey indicated there was also an increase in demand for both housing and consumer loans in the third quarter, after weakening in the previous quarter.

Reporting around the launch of the second phase of the government’s liquidity support for private businesses in the autumn suggested that big companies had already met their funding needs at that point, with SMEs still left suffering problems.

Despite the fact that 85 percent of the new loans disbursed in this phase through the government’s Guarantee Fund is earmarked for SMEs, the data through the end of November is not encouraging. A jump in net credit in the summer — a large portion of which went to the struggling tourism sector — suggested this bottleneck may have broken. But since then, the amount of new credit has declined each month to just 96 million euros in November, compared with 733 million euros in July.

This breakdown suggests there are parts of the real economy that are still starved of the credit they need to survive the pandemic. What the analysis doesn’t address is the ability of the non-financial private sector, in aggregate, to absorb that 40 billion euros of additional liquidity that the ECB has put at Greek banks’ disposal. This will be the subject of a post next week.

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback, either in the comments, on Twitter or by reply if you received the newsletter by email. If you’re not subscribed yet, consider doing so now.